By Tom

Hey! We’re not dead, we’ve been working on our documentary series “1982”. We released Part 2 last month, you can listen to it here. As we like to do, here is the written essay to it.

Whitey Herzog took over a Cardinals team in the midst of a lost season. They had just fired manager Ken Boyer after an 18-33 start that included a hellish 8-18 May record. Fresh off his dismissal from the Royals and no doubt still bitter from his public sparring with owner Ewing Kauffman and GM Joe Burke, Herzog thought of taking time away before getting the call to Grant’s Farm to meet with Gussie Busch. Busch and Herzog were both beer-chugging Germans who appreciated bluntness in the face of masked cordialities. Shortly after their meeting Gussie held a press conference and donned his new manager with a red Cardinals cap.

Whitey was trashed on the way out by the Royals front office, but what he didn’t expect was the parting shots he took from his team. As a man who prided himself on being a player’s manager, Royals stars like Hal McRae and Frank White offered no pleasantries to the White Rat. Center Fielder Amos Otis was said to be “jumping with joy” at the news of Herzog’s firing, telling the press “I had enough trouble with him. Let another team find out now. I think his hat size got too big for his head. I wish him luck as long as he stays in St. Louis instead of Kansas City.”

The cause for disdain came from Herzog’s insistence on trading six-year vet John Mayberry to Toronto for $70,000 cash. Mayberry was a popular presence in the KC locker room, beloved by teammates and fans. Allegedly, Whitey held a grudge over his first baseman dropping a foul ball in the recent LCS. According to the press Mayberry was still groggy after having a tooth pulled at the dentist, and while his stats no longer reflected his MVP runner-up 1975 season, he was a seasoned pro with a league average bat. The 15-year veteran scraped together a 120 OPS+ during his tenure playing under the White Rat.

This wasn’t uncommon behavior for Whitey. He benched fan favorite Cookie Rojas as soon as he took over from Jack McKeon. To play his style of game–Whiteyball–he had to assemble the perfect team to do so. He didn’t care about star power, legacy, or veternancy. He gave no quarter and asked for none, if he thought you sucked he let you know and he played the right guy for it. His main obstacle in KC was that he didn’t have the same power as his general manager, and the players he wanted would go somewhere else because the front office didn’t want to spend much money.

Against the backdrop of Whitey building this Cardinals team–a franchise that lost their competitive edge in recent years–is the decay of the American industrial base, the plummeting enrollment and power of labor, and the onset of unfettered capitalism. Despite this, one institution is going to rise up and become the most powerful labor union in the United States, and the man behind that is just as integral to the legacy of baseball as the White Rat or Gussie Busch.

It was a close call for the Cardinals, they almost left St. Louis for good. You may recall from Part 1 the story of Fred Saigh, who like all rich guys couldn’t help but cheat on his taxes. Saigh pleaded no contest to $19,000 in tax evasion, and commissioner Ford Frick gave him an ultimatum to sell the team.

We can sit here and laugh at Freddy boy, but it is kind of a bummer. Saigh and Robert Hannegan bought the team in 1947 from Sam Breadon. A couple years later Saigh would buy out his partner. Under Breadon the Cardinals won six World Series, including their first in 1926. Breadon had been renting Sportsman’s Park from the neighboring Browns since 1920 and had always dreamed of building one of his own. He couldn’t quite close the deal, despite setting back $5 million to do so. Stricken with prostate cancer and facing heavy taxation on that large wad of cash, he sold.

Breadon transformed the Cardinals from a pushover into a powerhouse, and with hall of famer Branch Rickey, built a farm system that ensured dynastic dominance during the 1940s. However, Saigh wouldn’t be so lucky, and that prized farm system was bled dry by the time Breadon sold him the team. Under Saigh the Cardinals never got their stadium or another crack at the World Series. They came close in ‘49, but the 1950s would be dominated by the Brooklyn Dodgers. At this time Brown’s owner Bill Veeck was doing everything in his power to undermine his crosstown rivals, despite them being the fan favorite. When news broke that Saigh was being indicted, Veeck was sort of relieved that his nemesis was gone.

Bill Veeck was not the kind of guy who didn’t talk shit, it was his best quality. Years ago he tried evicting the Cardinals from Sportsman’s Park, a place he built his personal apartment in. Weeks before Saigh sold the team to Gussie Busch, Veeck was warring with the Yankees over lost TV revenue, going so far as to threaten a lawsuit. After the Browns moved to Baltimore, Bill would pressure towns that housed his Spring Training and minor league squads to integrate or he’d pull his team. People tend to remember him for the infamous Disco Demolition Night or signing 3 foot 7 Eddie Gaedel to get a plate appearance—giving him the jersey number ⅛ in the process. Veeck was so much more than that, he was an ally during the Civil Rights Era and did everything he could to grow and expand the game.

Veeck had a hollowed wooden leg that came courtesy from his time as an artilleryman in World War II. The ex-marine lost it when a howitzer rolled over and crushed it. According to him he lived the rest of his life in pain, but he had a good sense of humor, drilling holes in his prosthetics so could use them as an ashtray. The venom he harbored for the Cardinals had waned. Perhaps this was a softening of Veeck. Who knows. But really he could see the writing on the wall.

In the weeks before the Anheuser-Busch purchase, the Cardinals were making plans to be bought by an ownership group out of Milwaukee. Talks had progressed so far along that staffers were given notices that their time with the organization would be ending unless they were willing to move to Wisconsin.

But right after Saigh’s sale, it was suddenly Veeck who was courting those offers and instead of banging the war drum he offered an olive branch to Gussie Busch.

Veeck long knew the importance of overwhelming firepower. He was the last of the baseball owners who didn’t inherit their wealth, building it from his time as a treasurer for the Cubs before buying the minor league Milwaukee Brewers. He could what lay ahead the same way a forward observer could see coordinates on a map. He knew he didn’t have the ammunition to match Anheuser-Busch’s wealth, and so he sold the Browns to Clarence Miles who moved them to Baltimore the following season. Right before that he sold Sportsman’s Park to the Cardinals.

Gussie Busch invested a lot of money into Sportsman, which was left in such a bad state that the city nearly condemned it. By 1959 the city worked out a deal for Busch to build a multi-purpose stadium after the NFL Chicago Cardinals moved in. Fun.

In the midst of all this capital getting tossed around, Fred Saigh was there. He didn’t go away forever, maybe he should have. After six months in the clink he got out and began buying up Anheuser-Busch stock. It was estimated that he owned about $60 million in shares with the company. As the Cardinals broke ground on a $24 million dollar stadium, Saigh harbored resentment for the way Busch and Veeck had treated him. He detested that he received hardly any credit for keeping the Cardinals in St. Louis, and felt that the organization played pitifully since he left. In 1964, their final season in their old park, the Cardinals were 64-56 and 9 games back in the division. With Busch Memorial Stadium being built on 31 blocks of downtown commercial district, Gussie let it become public that his organization was hemorrhaging money, and that if this team failed to draw 1.2 million fans the following season then the Cardinals may be in trouble.

After Busch fired general manager Bing Devine, Saigh penned a letter with a $25,000 check enclosed addressed to Gussie. He said, “The Cardinal organization has been so demoralized by an unprecedented military chain of command in front office management that those in positions responsible for a competing team were hog-tied to indecisions, debate and fear for their jobs which are held with the temper of your whims.” He offered to buy the team back for $4.5 million dollars and the check was made as a token of Saigh’s seriousness.

But this is Gussie Busch we’re talking about, and he promptly told Saigh to go fuck himself. And if that wasn’t enough the Cardinals got red hot and won 29 of their last 42 games to capture the NL Pennant from a choking Phillies squad. And because this is the ‘64 Cardinals we’re talking about, they dispatched the Yankees in 7 for their seventh World Series title.

They got their fans too. From 1965 to ‘71 they averaged over 1.7 million fans. In ‘67 and ‘68 they drew over 2 million. One of the first orders of business Gussie directed his front office to do was integrate the team, and while the Cards got burned when they traded for Tom Alston–on account that the San Diego Padres lied about his age by two years–they fielded a diverse and talented cast of black athletes. They picked up Curt Flood from the Reds who didn’t want to field an all-black outfield, they signed Bob Gibson out of Creighton college, they fleeced the Cubs for Lou Brock, they nabbed Bill White from the Giants and when he’d eventually leave they swindled the Giants again for Orlando Cepeda who’d go on to win a MVP for them.

The Cardinals were a fulcrum for 1960s America. While Gussie Busch loathed segregation, it cannot be said he integrated out of the kindness of his heart. The quickest way to get change from an employer is to threaten their income, which is what motivated Busch to trade for Alston when he grew concerned over a possible boycott. In Spring Training Bill White and Bob Gibson lived in separate housing due to Jim Crow laws, and it wasn’t until they went public with their treatment that Busch made changes. During their first three seasons with the team, Gibson and Flood had to endure the managerial whims of Solly Hemus, who would refer to them as you-know-whats and disparage them by saying they should find some other career to pursue; with Gibson he was exceptionally cruel telling him not to bother with pitching strategies as he wasn’t smart enough to grasp them.

The Cardinals rehired Bing Devine for a second stint after the 1967 season. Devine was a longtime front office man and would serve his second term until he was fired in ‘78. But you should also know that he retaliated against players like Joe Torre, Ted Simmons, and Curt Flood. In ‘69 Flood held out for a raise and got one, but Devine didn’t like him playing hardball and shipped him to the most racist city in the majors: Philadelphia. In return the Cardinals got Dick Allen, who endured so much racist shit from the Phillies faithful and press that he could fill a book. Flood had lived in St. Louis the last 12 years and owned a photography business and didn’t want to leave a city he had built his life in, so later that year he refused to report to the Phillies and filed suit challenging baseball’s reserve clause.

Flood didn’t win his case, but made enough of a stink that the MLBPA set their sights on tearing down the reserve system one brick at a time. After the Seitz Decision freed Dave McNally and Andy Messersmith from their respective clubs, MLB players could become free agents. The Cardinals celebrated by signing 10 free agents from 1977-1980 who generated a whopping negative 1.0 WAR.

The Cardinals spent the early 70s enjoying limited success but failing to capture the NL East divisional crown. At the end of 1976 they moved longtime manager Red Schoendienst out of the dugout and brought in Vern Rapp, who enjoyed one full season before losing the clubhouse so bad that Lou Brock staged an intervention to try and get him to be less of an asshole.

He told the team to stuff it and that he’d never change, and after a 6-11 start to the ‘78 season he was dumped and Ken Boyer was brought in.

In 1968 the Cardinals were said to have the highest payroll in the MLB, the first to crack a million dollars. After Curt Flood got a pay hike Gussie Busch directed Devine to tear down the house by trading promising pitchers Jerry Reuss and Steve Carlton, the latter making the grave mistake of demanding a $10,000 raise. Throughout the 70s the Cardinals highest earners were legends like Bob Gibson and Lou Brock, and after them Keith Hernandez with his half a million dollar salary and Bob Forsch who signed a 3 year $1 million contract after posting a 20 win season.

Whitey came in and saw excess in the Cardinals ranks. He viewed Hernandez as a troublesome player with a shitty attitude; he’d eventually trade Keith to the basement-dwelling Mets in 1983 after he jogged to first on a double play. While he retained Forsch it was only barely, as Gussie would insist that if he wanted to keep a large salary he’d have to get rid of another.

All this would start a series of sweepstakes the minute Whitey moved from being the manager, to taking over for John Claiborne as General Manager, and when he wasn’t satisfied with that, he wore both hats and engaged in two offseasons of some of the most wild and zany trades. It was 100% Whitey, but in the backdrop loomed a deeper history that permitted him the chance to dump dollars and pick up the guys he desperately sought to build the Runnin’ Redbirds, it was all thanks to a man who spent the better part of 16 years building baseball as we know it, and while Whitey respected the man insofar he got his pension, he never really appreciated what he did for the game.

This series doesn’t have good or bad guys in it. I would say it barely has protagonists. All these stories are real and happened, you know how this ends if you go to the internet or download a book.

If anything we want this series to always be more than just a rundown of some World Series teams and their accomplishments. We want to talk about Keith Hernandez’s time growing up working class, how he got his big break based on a gut feeling by Bob Kennedy. We want to talk about the idiosyncrasies of Lonnie Smith and Joaquin Andujar, Darrell Porter’s triumph over drug and alcohol addiction, Glenn Brummer fucking going for it on a blistering August afternoon. We’ve spent a lot of time talking about the suits, but we’re going to spend more time talking about these players as this series goes on.

What we want you to know is that none of these incredible stories wouldn’t be possible without labor. You can call us communists and you’d pretty much be correct, but no one shows up to a crowded baseball game to watch Bill DeWitt or Oli Marmol. And while he sure as hell was popular, nobody got their family together to buy $6 tickets to go watch a team play on a plastic field because they were there to see the White Rat.

It took this man decades to get the recognition he deserved. He stepped on every owner’s toe at some point, and by the time he was rightfully elected by a Veteran’s Committee on his eighth try he had been dead for 8 years.

Marvin Miller spent his life cutting his teeth as a force for labor. As Whitey was readying for the 1981 season Miller was mobilizing the player’s union for an impending showdown with owner’s over free agency. The previous year, the owner’s had begun stockpiling funds and bought insurance in the event of a strike. Their previous negotiator, John Gaherin, was a respected statesman in the eyes of Miller. But they dumped him and brought in a shrewd ball-buster in Ray Grebey.

Miller was used to guys like Grebey. His entire life was centered around conflict and labor, from his upbringing where he’d stand on picket lines, to his work for the International Association of Machinists or United Auto Workers. He began working for the United Steelworkers in 1950 where he became their chief economic adviser and assistant to the president.

In 1965 he sat across a table from MLB players Robin Roberts, Jim Bunning, and Harvey Kuenn. Miller was interviewing for the role of executive director of a union that was so pitifully weak. It was a company union, operating at the behest of the owners who would kick a little money into a pension fund that hardly meant shit. Players during that time had no bargaining power, and because MLB twice won court cases over the issue of interstate commerce, couldn’t be safeguarded the same protections workers had under the Sherman Act. The last real attempt at unionizing came from the American Baseball Guild who failed to enact a strike in 1946 and was squashed by ownership.

Miller wasn’t the first choice to run the MLBPA, the job initially went to incumbent John Cannon who pissed off the union members so badly they withdrew his consideration and went with Miller. In Marvin’s eyes he had a tough road ahead; for one baseball players during this time hardly knew their labor rights. This was despite more players coming out of college or middle class backgrounds in the 1960s. There were some holdouts of course, but a player that did this had to have some serious starpower. In 1966 Sandy Koufax and Don Drysdale held out after learning that GM Buzzie Bavasi pitted them against each other to get a lower salary. Their gamble paid off and they received 3 year contracts at $125,000 and $110,000. If you want to know what the change equates to, imagine if Max Scherzer or Jacob Degrom held out to receive just over $900,000.

Miller had touted that MLB players were among the most exploited workers in the country, he compared them to fruit-pickers. Managers and players were more concerned if Miller was a communist or if he’d been investigated by the FBI. In one interaction Miller was challenged by Yankees pitcher Jim Bouton about the reserve clause when he asked him that without it, wouldn’t the wealthiest teams buy up all the stars? He replied, “You mean like the Yankees?”

Miller admitted he didn’t know a lot about baseball economics at first, but he would kick himself if he didn’t give it a fair shot. He won election in a landslide from players and set about establishing the Union’s first CBA. To shore up funds he struck a licensing deal with Coca-Cola and filed suit against Topps. In retaliation MLB owners withdrew funding from the union. The first victory for baseball labor came when he got the owners to contribute $200,000 more annually to the MLB pension fund. The following year the union ratified their first CBA that saw their minimum salary increase from $7,000 to $10,000, a huge pay increase for one-third of the players at the time. They also got a $15 increase to their $25 stipend during Spring Training, a figure that had been in place for twenty years until Miller arrived. They enacted their first successful work stoppage when they struck for 13 days over arbitration, pensions, and higher salaries, the latter of which caused Gussie Busch to shout, “We’re not going to give the players another goddamn cent. If they want to strike, let ‘em!”

In the coming years Miller and his union would win the right for arbitration hearings to be conducted by an impartial judge instead of the commissioner. Players saw an increase to their postseason bonuses. After his trade to Philadelphia, Curt Flood filed suit against MLB’s reserve clause claiming it violated antitrust laws. While Miller understood it was likely a losing battle, he knew every case had the potential to shift the needle further away from the owners and closer to the players. Thanks in large part to 4 recently confirmed Supreme Court Justices under Richard Nixon, Flood lost his case 5-3, with one of the justices recusing himself because he owned stock in Anheuser-Busch. Despite this setback Miller’s influence in the MLB had expanded to the NBA and NFL, Puerto Rican ballplayers formed their own union and threatened to strike for higher pay, and in the Mexican League players were organized under the Confederation of Workers.

Around this time comes a possible antagonist in commissioner Bowie Kuhn. Kuhn served as legal counsel to the National League before slipping his way into the role of commish after the departure of William Eckert. Kuhn was a hard-nosed conservative who’d enact a no-tolerance policy for gambling and drugs. Baseball flourished during his time, seeing attendance double and millions generated from TV revenue. The league expanded by four teams, and with that came over $30 million in entry free revenue for the rest of the league. Kuhn was confident he could get the best of Miller, but he rarely ever did.

Their relationship, while rarely harmonious, wasn’t always filled with spite. They had no trouble meeting together, even though Miller saw Kuhn as a pompous dullard and Kuhn saw him a socialist rabble-rouser. But there were moments of cooperation, like in 1969 when Kuhn ordered the owners back to the negotiating table to settle on pensions, or in 1976 when he ended an owner backed lockout during Spring Training.

Following Flood v. Kuhn Miller went to work on a new CBA that raised the minimum salary to $16,000 by 1975. The 10 and 5 rule was established, pay cuts were limited, and the pension fund increased by a further $300,000. They won impartial hearings and the dissemination of salary information. After Charlie Finely violated a contract clause with his star pitcher Jim ‘Catfish’ Hunter, the union won their hearing and had their first free agent. The following year, with Dave McNally and Andy Messersmith playing without contracts, Miller challenged the interpretation of the reserve clause. The arbitrator, Peter Seitz, nullified the reserve clause and made McNally and Messersmith free agents. After almost 100 years, MLB players finally had won their emancipation. After a lockout and an exhaustive appeals process, the owners accepted free agency and ratified a new CBA.

With the latest CBA expiring at the end of the 1979 season, MLB owners were gearing up for a showdown. Minimum salaries reached $21,000 for the end of the year, the average MLB salary sat at $113,000, and modern free agency was being molded. Under the 1976-79 CBA, players qualified for free agency after six years of MLB service time. Baseball teams could only sign as many free agents as they lost, and if they signed a free agent that player’s former team was entitled to draft compensation; a first rounder for team’s in the top half of the league, and a second rounder for those in the bottom. Players could only negotiate with no more than 12 teams at the time, who had to acquire rights to negotiation through a re-entry draft, this one, while short lived, is going to be important for Whitey Herzog in acquiring his favorite player.

The strike nearly happened a year earlier. In 1980 MLB owners were gunning for the autonomy that players spent the past decade fighting for. MLB wanted to eliminate salary arbitration and replace it with a pay scale for a player’s first six seasons, but more concerning they wanted further compensation during free agency. If a team signed a free agent then they’d have to give up, not a draft pick, but an MLB ready player and could only protect 15 of the 25 men on their roster.

In layman’s terms here, imagine you leave a job, but the new job you apply and get accepted for requires they send someone with your experience back, maybe another person as well. This maneuver would undermine what free agency is about, and in turn dissuade players from not only fair bargaining, but also limit who would talk to them, because signing a guy like Darrell Porter may mean you give up a Keith Hernandez or Dane Iorg, or perhaps a prospect that you had scouted and spent years developing like Tommy Herr.

The union met this response with outrage and set a strike date for May 22nd, however Miller and Grebey met behind closed doors and drew up an interim plan to forestall the impending labor stoppage until next season.

When the interim CBA expired the owners had amassed $15 million in their strike pool along with further insurances that would cover up to 40 games lost. The Union set aside over $1 million in licensing revenue to assist players. A last second meeting occurred on June 10th but made no headway, and two days later the Union walked off the job and the strike began.

Union players were not immune from retaliation. Every step of the way Gussie Busch and his fellow owners did their best to throw roadblocks in front of players. Curt Flood was traded in retaliation, same with Steve Carlton. Braves GM Paul Richards docked Joe Torre 20% of his salary and traded him to St. Louis for his union status.

Ted Simmons almost became a reserve clause candidate when he held out for $35,000 in 1971, this prompted Bing Devine to conspire to trade him and while Simmons was shopped around the threat of another court fight deterred potential buyers and Simmons got his raise.

. Jim Bunning was traded almost immediately after the Union’s founding; the same with Al Downing and Ron Santo. The 1971 offseason was a bloodbath as owners found a way to rid themselves of union delegates by trading, releasing, selling, or intimidating 19 of 24 representatives. Future Hall of Famer Fergie Jenkins was busted at the Canadian border with a shit ton of drugs, but the Union stepped in and filed a grievance and Jenkins avoided any penalization, not to mention the doubts raised that the drugs may have been planted. Yet despite all this bullshit, Miller’s union held the line.

Labor in America had been on a downward trend. Occurring almost simultaneously was the Air Traffic Controllers strike which saw over 11,000 PATCO members walk off the job in retaliation to long work hours, harsh working conditions, and shitty pay. They struck in August and when a deal couldn’t be reached with the FAA, Ronald Reagan fired all of them and decertified their union. We saw something similar today when over 100,000 railroad workers threatened to strike. For something as small as sick days, man. And what happened? They were forced back to work.

This is the ending of a period in America called the Long Seventies, a 16 year span from 1965-1981 that saw waves of labor disputes. These strikes occurred in the automotive, steel, airlines, and postal industries. They occurred everywhere and all wanted variations of the same thing every worker should have: dignity. Black steelworkers struck for integration; so did Memphis garbage men in the late 60s. Marvin Miller’s most eager supporters came from black and latino ballplayers who endured endless discrimination in Florida during Spring Training.

And what happened to these guys? Coal miners that struck in the 1970s lacked the resources and manpower they had in the 1950s, when they had four times the number of members. The United Automobile Workers had 1.5 million members before the turn of the decade, but today their memberships are not even 400,000.

What Ronald Reagan did to the PATCO would become an omen for how labor would be treated the rest of the century. In a bizarre way, it’s sort of miraculous that Marvin Miller’s union survived at all.

While the threat of the strike loomed, Whitey Herzog began amassing his team. He had rallied the Cardinals from the NL cellar to a modest 56-69 record before being summoned back to Grant’s Farm to meet with Gussie Busch. Whitey admitted he was pretty reluctant at first, and wasn’t sure how he’d adjust to being off the field and behind a desk, but in the end he always reciprocated loyalty with those who showed it.

He also wanted total control over his team, a function he lacked when he was with the Rangers and Royals. He told the press after accepting the GM job that, “I don’t want to manage the Cardinals if I don’t have control of my own destiny.” Rick Hummel called it when he said that Whitey wouldn’t be able to keep himself from the dugout for too long. While Red Schoendienst returned as interim manager he made it very clear he didn’t want to do this beyond that season. Whitey began his search for a guy just like him, considering poaching his long time friend Dick Williams from the Expos or Don Zimmer from the Red Sox. He inquired about former colleague Chuck Hiller, despite his authoritarian approach leading players to call him Chuck Hitler. Gene Mauch was available after he resigned from the Twins and according to the press embodied Herzog’s hard-nosed managerial style.

Throughout September and October the Post-Dispatch hounded him on “who’s it going to be?” And every time Whitey would kind of kick at the dirt and say something like I’ll know by the end of the week or the World Series! He promised that, it’s in writing “CARDINALS MANAGER WHITEY HERZOG SAID MONDAY NIGHT THAT HE WOULD HAVE AN ANNOUNCEMENT ON A NEW MANAGER BY THE END OF THE WORLD SERIES” and he promised everyone it would not be him.

Whitey, who the are you kidding?

He scheduled a goddamn press conference a week before announcing he was going to manage the club. He disclosed that he had a meeting with Gussie in the weeks prior and had his confidence. The only thing he regretted about taking both jobs is that he couldn’t spend this time of the year fishing and hunting. Just before his announcement Whitey had been laying out his upcoming philosophy beginning with dumping excess salary and attitude and bolstering his pitching staff. He wanted guys who played hard, took the extra base, legged out grounders, and broke up double plays by going into the bag hard. So naturally, he tried to trade Keith Hernandez.

He’d eventually ship Hernandez to the Metropolitans years later, but the Mets were interested in Hernandez as early as 1980 when Rick Hummel broke that Whitey had offered the co-MVP for a slew of their pitching talent. Hernandez was maybe the most vocal member on the team and for that has a slew of amazing quotes, you could always count on Keith’s honesty, and by honesty I mean him being sort of a dick. When asked about rumors he’d be traded he said he’d come back to haunt this team like Steve Carlton, and that when it came to not giving 110% he pointed out that he led the NL in runs in consecutive years. And because Keith Hernandez had a penchant for throwing someone under the bus he said he was one of four players who dogged some grounders. Way to go. But Keith had an incredible knack for delivering the truth, and one of his more truthful moments that offseason was saying that this team, which led the National League in runs scored, needed a stopper and that someone big was going to have to go to get him.

Someone big could be anyone except one guy and that was Garry Templeton. Whitey stated that he was the one guy who was untouchable in the offseason, jokingly because he didn’t have a backup shortstop. He was also fond of a lot of guys, like second baseman Ken Oberkfell, who was excited to have Whitey back after lamenting earlier in the season of his role change.

Before he took on the dual role, one of Whitey’s first moves was inking longtime Cards starter Bob Forsch to a 6 year $3.5 million deal. Forsch was drafted in the 26th round of the 1968 MLB Draft as a third baseman where he soon realized he kind of stunk, so he converted to pitching and after four years made his debut in 1974 where he stuck the rest of his career. He won 20 games in Vern Rapp’s first season and the following year tossed his first career no-hitter against the Phillies, despite what appeared to be a hit off the bat of Garry Maddox being changed to an error on third baseman Ken Reitz, thanks in large part to official scorer and comrade Neal Russo.

Whitey was in search of pitching that could shore up a porous Cardinals staff that finished in the bottom 4 of fWAR. While a man ahead of his time, Whitey didn’t want to improve a staff with the third worst strikeout percentage, but their luck on balls in play. For over a month the Cardinals were linked to the San Diego Padres on being close to sealing the deal for legendary fireman Rollie Fingers. The Friars initially had their sights on the young and scrappy Tommy Herr and upcoming catching star Terry Kennedy. Whitey even told the Post-Dispatch that he didn’t think he’d pursue it.

But in typical Whitey fashion, he was bullshitting everyone. Around this time that Marvin Miller and Ray Grebey were sparring over free agency compensation, Whitey took advantage of the MLB re-entry draft to sign one of his favorite people in Darrell Porter.

Porter was Whitey’s primary backstop the last three years of his stint in KC. He had power but most importantly a fantastic eye. Whitey wrote about Porter’s discipline, and that if he hit .230 for you he’d have an on-base percentage of .380. Among players with at least 4,000 plate appearances from 1970 to 1980, Porter ranked 11th in walk percentage and his .356 on-base percentage for that span was topped by only three other catchers, one of whom being Ted Simmons. Porter was one of the more distraught players when Whitey left the Royals, and for good reason. Porter and Whitey hung out a lot, often fishing and hunting together in the offseason. When Porter completed his first rehab stint, Whitey took him on his boat to catch bass.

Whitey says he picked up Porter because he wanted that reliability of a veteran guy who played the game right. He cited Porter’s defense, pointing out that current catcher Ted Simmons’ defensive woes as a massive liability. For the decade, Simmons led the majors in passed balls, and was also challenged the most on the basepaths with opponents swiping 918 bags in 1,404 attempts against him. While rumors of Simmons’s glass arm were maybe a little exaggerated, Porter had a fucking rocket launcher attached to his shoulder throwing out runners over 40% of the time.

This loyalty netted Porter a 5 a year $4,000,0000 contract, making him the highest paid catcher in the bigs. It also created a new problem with his current teammate Simmons. The Cardinals already sported 3 catchers and were adding a 4th, but when asked about it Whitey said, “he needed them to make deals.” Around this time Herzog was linked with the Cubs on trading for closer Bruce Sutter, and had attached 1st rounder Leon Durham to the deal and a very angry Ken Reitz. Reitz had gone through the ringer with this team, being signed to a 6 year deal back in 1979. Advanced stats today portray Ken as barely replacement level, but this was due to his bad bat.

Defensively, Reitz was arguably the second best third baseman of his time behind Hall of Famer Mike Schmidt. He had just come off a season where he set the lowest mark for errors at the hot corner with 8. Whitey wanted to dump Reitz’s bat and most importantly his contract, the move pissed off the third baseman so much that only his wife convey his frustration to the press.

A day after signing Darrell Porter, Whitey pulled off his first blockbuster trade when he finally pulled the trigger with the Padres. He traded 5 pitchers and 2 catchers in exchange for Rollie Fingers, Bob Shirley, and Gene Tenace. There goes the catching logjam. Of the 7 guys Whitey shopped, only Terry Kennedy played beyond 1983 and would go on to have a fairly remarkable career.

But wait there’s more! Not even 24 hours later, Whitey convinced Ken Reitz to waive his no-trade clause with a $150,000 parting gift to buy it out, and shipped him along with Durham to the Cubs for Hall of Famer Bruce Sutter. Sutter had always been Whitey’s target for the offseason. The Padres trade was fanfare, to hear Whitey say it he wanted to trim the fat and use what he got to get other pieces.

Whitey is the ultimate MLB The Show GM. If you ever play that game’s franchise mode and roll your eyes at some of the trades that occur in that game, understand that Whitey Herzog did far wackier shit thirty years ago. Nothing is too far-fetched, everything is on the table.

But he wasn’t done, not by a long shot.

After signing Darrell Porter, Herzog asked his two stars in Simmons and Hernandez to change positions. He wanted Simmons playing first base and Hernandez in left. While Simba told the press he was fine with it, privately he detested the move, going so far as to request a trade from his GM. He preferred going to a team where he could catch 100 games and DH 50. When asked if such moves would rub people the wrong way, Whitey said he didn’t care, if they didn’t play where he put them he’d trade them. Simmons and Herzog would have an acrimonious relationship for the better part of a decade after this, but eventually made amends when the aging and soon-to-retire catcher approached Herzog in Atlanta and asked him what he should do after baseball. Whitey said become a farm director and that if he could do it he was sure Simmons could. There’s this real touching article by Rick Hummel that highlights both men’s warmth to one another. Simmons wasn’t as bitter as he used to be. He took Whitey’s advice and became the Cardinals farm director and then became the Pirates GM for a time. He told the White Rat he owed him so much; that he gave him his life after baseball.

But before all this, he probably wanted to kill him. Simmons got a bad rap from management and the Cardinals press, who felt that his mind was sometimes anywhere else but the diamond. I can’t speak about Simmons’s heart too much.

There was the contract holdout that nearly got him traded early in his career. He essentially got ex-manager Vern Rapp fired when it leaked that Rapp referred to Simmons as a “loser.” Simba was anything but that, but he did play on a bunch of losers his whole career.

From 1970 to 1980, Simmons started, played, and caught the most innings at his position. He caught more than Fisk, Munson, Boone, Porter, and Bench. While he struggled with his defense early on and right before he left, he was a solid arm behind the dish in between. He played tired, hurt, and exhausted and the Cardinals never did him the honor of finishing higher than 2nd place. His 49.2 fWAR placed him second during that span. He led all catchers in hits and batting average. He was runner-up or top 5 in stats like OPS, runs scored, and runs batted in. Aside from Hall of Famer Johnny Bench, Simmons was hands-down a generational and remains to this day the only Cardinal taken in the 1st round to make the Hall of Fame.

But almost immediately after acquiring Rollie Fingers, and with one contract to shave off, the ax fell on Simmons. Not even four days after the Padres trade, he was traded with Fingers and Pete Vuckovich to the Milwaukee Brewers for pitchers Larry Sorenson, Dave LaPoint, right fielder Sixto Lezcano, and promising outfield prospect David Green.

The Brewers had to dig up a ton of cash for Simmons, about $750,000, for the final three years of his contract. If the Cardinals didn’t want him, someone else surely did and they paid a heavy price for it. It almost didn’t happen, as Whitey wanted a 40 man pitcher and their top prospect in Green. But the Brewers had a small window after three previous seasons saw them win 274 games with nothing to show for it. They had two Hall of Famer hitters in Robin Yount and Paul Molitor, and by the time their window would close they’d have power hitters in Ben Oglivie, Gorman Thomas, and Cecil Cooper. The trade made them among the favorites in the American League, with manager Buck Rodgers saying they were definite contenders, and maybe, as a parting shot to the Cardinals, bragged that his team had received the best catcher in the game.

Simmons was beside himself but said it had to be done. He vowed that there were no hard feelings, even going out of his way to express that the deal made sense. He thanked a lot of people, but mostly he thanked Gussie Busch. Gussie reciprocated, but maybe had the best line when it came to his GM saying that Whitey, “Talks a helluva lot, but he’s not a con artist. By God, he came through with the truth.” The White Rat didn’t mind trading a franchise cornerstone and beloved fan favorite, he said he understood that moving Simmons to first and Hernandez to left might create a lot of unneeded pressure. Hernandez was, and is, arguably the greatest fielding first baseman in the history of the game, a standard he alone set. In later years Whitey would say that if the NL had the DH, Ted Simmons would have been a Cardinal for life.

Here’s a joke by Bill Kurtzeborn for you: If Abbott and Costello had a tough time figuring out who’s on first, they should try to keep up with Whitey Herzog.

Whitey spent the rest of the offseason dumping Bobby Bonds’s salary and rounding out his coaching staff. Near the end of January he inked Sutter to a 4 year $3.5 million contract. His 1981 squad was set but not perfect. Whitey took some shots from fans for his Simmons trade, one going so far to say that he put the Brewers in a great position to beat the Yankees, something he could never do. Tom Barnidge wrote a whole column saying that Whitey broke up a scary and formidable offense, one that led the NL in scoring. Shit, he was even getting flamed on stage by comedians. I’ve been present at a few comedy clubs where comedians roast Mike Matheny or Mike Shildt. But c’mon, Whitey Herzog? St. Louisans acted like he shot their dog and smacked their mother on Christmas. But if you ask the White Rat he was sure he had a winner.

When it comes to labor nobody was a winner yet. Ray Grebey says that 21 of the 26 clubs failed to turn a profit last season, the blame lying with rising player salaries caused by free agency. Card reps Bob Forsch and Bob Sykes didn’t buy that, with the latter saying that if salaries were killing the game they’d happily lower them, but the owners don’t share their expenses publicly, something that is still a problem in today’s game. With a strike date expected to be set between March and June, Rick Hummel asked the newly minted Bruce Sutter what he thought. Sutter was set to lose $6,000 for each game lost, but the closer didn’t hesitate. He said he owed everything to the union and was on Marvin Miller’s side the entire way. To go a step further Sutter brought up the guys in 1972, saying “they went out on strike for us, we have to do the same.”

Whitey, to his credit, didn’t pick a side but had no trouble voicing some kind of opinion. He definitely believed that rising salaries were killing the sport and that small-market teams like the Minnesota Twins wouldn’t be around for long–fun fact, they still are and they’ve won two World Series–and that the owner’s couldn’t work things out because they themselves didn’t trust one another. But he also said that he understood why the player’s felt the way they did, and who wouldn’t want to make more money? As centrist of a contrarian as you can be.

A strike date was set for May 29th, between then Whitey’s ‘Birds got off to a 9-3 April and sat tied with the Phillies when the deadline approached. At the Union’s behest, the NLRB granted an injunction to open the owner’s books. While that made its way to a federal judge the union pushed the strike date back. The Cardinals finished May 23-17 and a game behind Philadelphia. They’ve only entered June with a winning record 3 times in the last 10 years.

Whatever concerns the press had about the offense were hushed at this point. Whitey’s team had a .719 OPS, good enough for 8th in the league. Their 195 runs ranked them 4th in MLB and 1st in the NL, and while they were still a year away from lighting the basepaths on fire, they ranked 5th in baseball with 44 stolen bases. The pitching had improved some but still ranked 19th in runs allowed, however the Bruce Sutter trade was already paying dividends as their 12 saves tied them for the NL lead.

As June rolled over the Union set a strike date for the 12th and talks dissolved to the point where no mediation could salvage their disagreements. The injunction was shot down by a federal judge on the 10th. Two days later, right after the Cardinals wrapped up a series win against the LA Dodgers at home in front of 40,000 fans, the strike commenced.

The mood in the clubhouse was solemn frustration, but the Cards stuck together. Bob Sykes said it was time to put up or shut up, Garry Templeton said the owners had 18 months to be serious, but waited until the last 2 days. Tito Landrum said it was a lot of hot air and flamethrowing right hander Mark Littell remained hopeful that things will get done in the same way you feel pressure with a runner on second and the game on the line. A timezone away, Pete struck out three times in a game that featured Nolan Ryan and Steve Carlton dueling into the 8th inning, but in his first at-bat he singled to center to tie Stan Musial’s NL hit record. Back in St. Louis the Cardinals are in awe of the screwball throwing Fernando Valenzuela, who punched out 9 in 7 innings, but they found a way to beat him 2-1. Tomorrow nobody will play baseball. Management remains hopeful that a deal will come to fruition and games will resume then, but player reps throughout the league say that’s not going to be the case. The only guy in management who seems to be in reality is Whitey, who tells the press he’s going to travel and and fish while all this is going on.

After about 250 games are canceled, Orioles’ owner Ed Williams gets enough of his colleagues on board to force an owner’s meeting. They met five days later on July 9th and began to show cracks in their defenses by privately admitting they were losing confidence in their chief negotiator Ray Grebey. A month from now, their strike insurance would run out and in three days the All-Star game would be lost. The Players remained strong in strike but were starting to show wear and tear. For some of them, they were losing $181 per day, and for stars like Dave Winfield that number was closer to $7,800. Dennis Eckersley publicly condemned the strike and said he just wanted to play ball. Union reps were holding rallies and meetings to maintain their resolve. Miller knew he just needed to keep his men together until early August.

Perhaps the owners sensed the player’s resilience. As the strike lasted through July owners began realizing that the Players weren’t going to budge, and that the money they’d make late summer from attendance, concessions, TV contracts, and the postseason, would all go away. On day fifty American League President Lee MacPhail summoned Grebey, Miller and his counsel Donald Fehr to his office for a private meeting. After two days Miller and Grebey hashed out a deal to end the strike.

The end result was so stupid and pointless. During the press announcement Miller refused to shake Grebey’s hand, he was so pissed off at him for doing this shit. It’s so fucking dumb that when the next CBA rolls around it’s removed entirely.

Okay, so you’re applying for a new job and you get the new job. Now, your old job wants compensation for your absence, but luckily they don’t have to take anyone from the place you now work at it. Thankfully, for them, there’s a pool of talent they can randomly take from someone else.

I guess in the grand scheme of things of how the American economy works, someone is taking something from someone else, and you could say the same about the workforce. The new CBA creates two classes among players, Type A who are in the statistical top 20 percent of their peers, and Type B who are in the top 21-30 percent. A player pool is created where teams can protect up to 24 of their 40 man roster, leaving the rest subject to compensation in the event a team loses a Type A player. Only one player can be taken from a team. If a team loses a Type B player they will receive two amateur draft picks.

Baseball clubs lost over $120 million in revenue and strike insurance from the stoppage, players had sacrificed $30 million in wages. While the owners had won small gains in player autonomy, the Players held strong, even as Ronald Reagan fired over 11,000 air traffic controllers days before play would resume. When the season picked back up on August 9th, Bowie Kuhn made a temporary change to the season’s format.

Kuhn decided to divide the season into halves. This would create a series of problems, such as teams playing more or less than their opponents. There was a similar SNAFU over the 17 day work stoppage in 1972 which featured the 86-70 Detroit Tigers winning the AL East Division over the 85-70 Boston Red Sox.

The split season was Bowie Kuhn’s idea. He was largely absent from the strike negotiations and later that year he would receive a vote of no-confidence from the owners. The split season would feature the winners of each division in both halves squaring off in a league divisional series, followed by the LCS and then the World Series.

The end result featured the two best teams in the National League missing the postseason. The Cincinnati Reds finished 66-42, but came in second behind the Dodgers and Astros. In the NL East the Cardinals shared the same fate, finishing 59-43 and missing the postseason by a half game to the 2nd half winning Expos. The day they were eliminated Whitey suggested they’d play a mini-World Series against the Reds. I’m sure he felt that old chip on his shoulder again. Last season the Royals he spent 5 seasons building made it to the World Series where they lost to the Phillies in 6. Those same Royals bumbled asshole first into this postseason with a 50-53 record because they won the 2nd half of their division. At least he didn’t have to see Billy Martin’s Yankees make it that would have been deva–

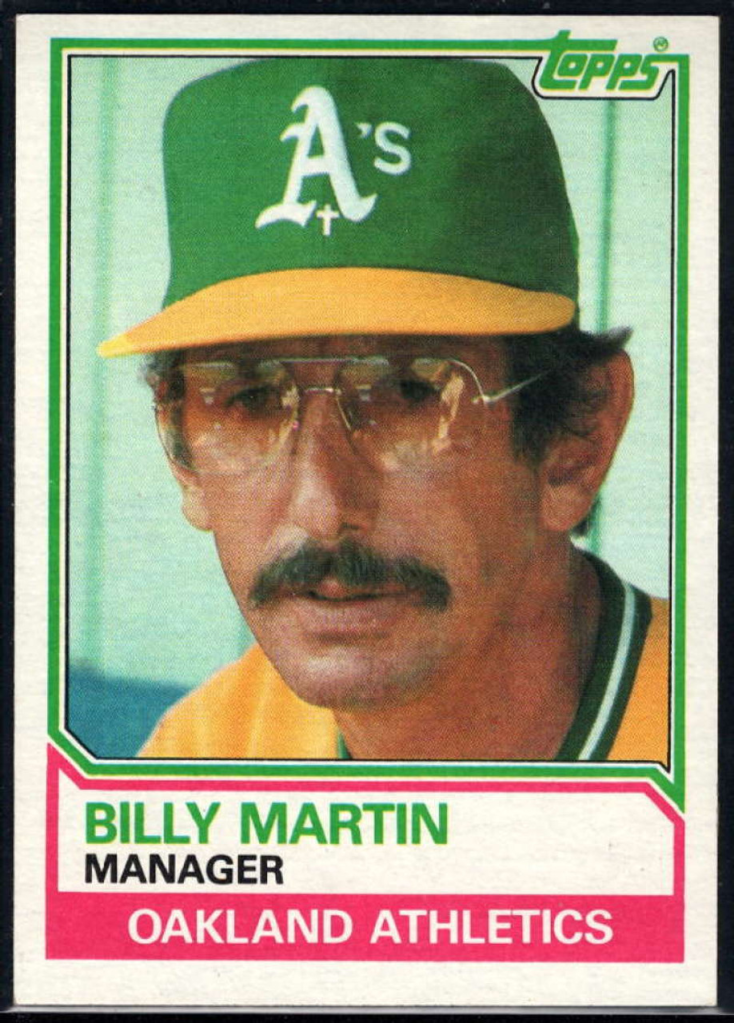

Oh wait, of course he did. Hold up folks it’s Billy Watch. We here at Worst Fans Incorporated believe that derailing an already 60 minute plus podcast special that’s taken 6 months to research and write is totally justified when it involves Billy Goddamn Martin, who got fired and then rehired by George Steinbrenner in the course of a season. Well actually he resigned the first time because he wanted his contract paid, which is cool and you should do that to any boss you have at any job. He did this because he got his heart broken by Steinbrenner who was in talks with White Sox owner Bill Veeck to trade Martin for manager Bob Lemon. I’m going to say that again, George Michael Steinbrenner III wanted to trade his manager for another team’s manager in the same League. Lucky for him Veeck fired Lemon who took over for the ailing Martin and guided the Yankees to an improbable 48-20 mark that ended with Bucky Dent winning the division in a game 163 over the Red Sox. The Yankees would beat the Dodgers in 6 games to win the World Series that year.

But wait there’s more! There’s so much more. Steinbrenner immediately regretted his decision to hire Lemon, so he planned to bring Billy back over the guy who led his team from 10 games back to win a championship. Oh well, Steinbrenner demanded Billy keep his cool and stay out of trouble while they made plans to dump Lemon, but this is Billy Fucking Martin we’re talking about so of course he got into a fight with a reporter at a basketball game in…Reno, Nevada? Holy shit, this guy is like if a five year-old wrote a My Name is Earl episode. Lemon’s Yankees got off to a 34-30 start so Steinbrenner said screw it bring on the Billy Goat who improved the team but not enough to make the playoffs. Oh, and because this drunk five year old is still writing bangers, Martin lost his job at the demand of Bowie Kuhn because he got into a fight with a marshmallow salesman. LET ME CLEAR MY THROAT AND SAY THAT AGAIN. World Series winning manager Billy Martin got into a fight with a MARSH-MALLOW-SALES-MAN.

Would you like to know more? Of course you do. The salesman’s name is Joseph Cooper. He is in Bloomington, Minnesota on a business trip, possibly selling marshmallows. He and his buddy run into Howard Wong and Billy Martin. They’re introduced. Billy is very drunk. He is also dressed in a cowboy hat and western attire. They start talking baseball and Joseph Cooper the marshmallow salesman says Dick Williams and Earl Weaver deserve manager of the year awards and this sets Billy off.

He begins by saying both managers are asses, and then says he’d like to go outside and kick Cooper’s ass. Cooper is 52 years old and six feet tall, taller than Martin, he also is a marshmallow salesman, which Billy finds out and starts laughing at him about. Joe Cooper ignores him and says that everybody reacts like this, that his job is a big joke, but Martin won’t stop.

He starts calling him Joe Marshmallow and then proceeds to slam 5 individual $100 bills saying that he could knock Cooper on his ass. Cooper ignores him but eventually Martin pisses him off so bad he takes him up on the offer. What Martin initially told the press is that Cooper tripped, but what came out is that as they walked into the parking lot Martin turned abruptly and punched Cooper, requiring him to need 9 stitches to close a busted lip. When Bowie Kuhn found out that Billy Martin punched a marshmallow salesman, well he probably laughed, but after that he called George Steinbrenner who fired Martin 5 days later.

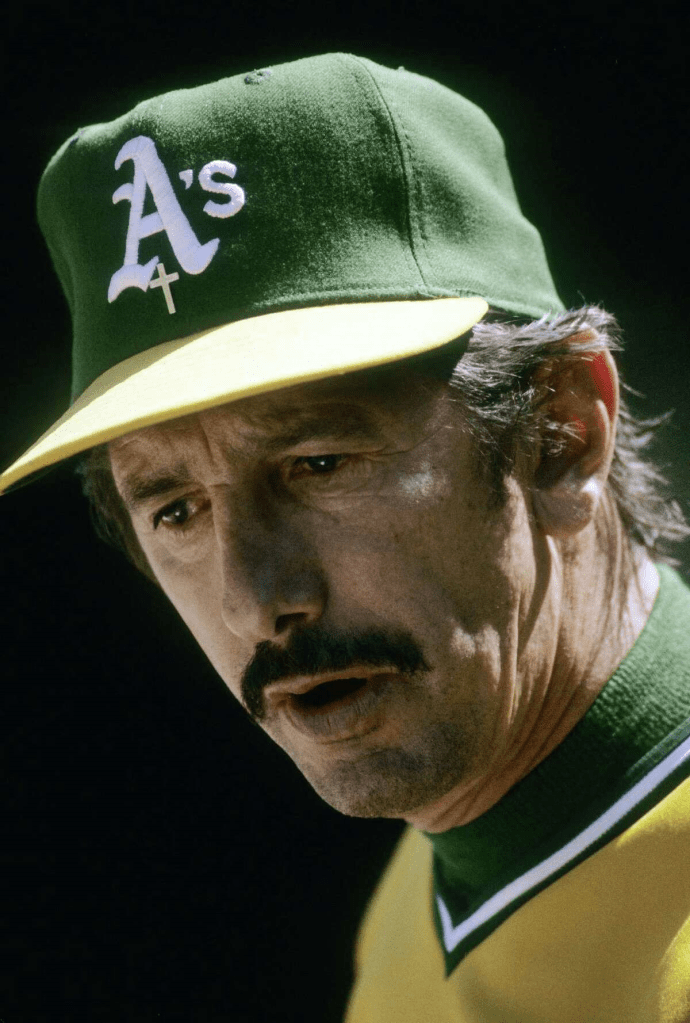

Hold on, the dudes are still rocking. You figure a radioactive guy like Martin wouldn’t manage another game again and you’d be mistaken! Frugal King Charlie Finley hired Martin to guide an A’s team that finished 54-108 the year before, and as is typical in a lot of Billy Martin rebuilds they improved immediately. One of his first interactions with the team, ALLEGEDLY, was introducing Claudell Washington to one of the hi-five inventors in Glenn Burke. Burke was also the first openly gay baseball player, but instead of saying, “Hey this is Glenn, he did that thing with Dusty Baker” he purportedly said, “This is Glenn, he’s a f—–.” When Burke went down with a knee injury Martin had him demoted to the minor leagues and on another occasion cut player Derek Bryant because he mistook him for Burke by saying, “Get that motherfucking homosexual out of there.” The A’s went 83-79 in 1980, and newspapers were coining the Athletics new aggressive style of play “Billyball.” In 1981 his Athletics finished with the best record in the American League and after dispatching the Royals in a 3 game sweep faced off against the New York Yankees who swept them.

You know how this is going to end. Billy is going to self sabotage, his team is going to underperform, he’ll call the president of the team the son of a whore or threaten to kill every players’ dog or some shit. But how it ends in Oakland perfectly coincides with the end of this script, and while there’ll be future Billy Watches in this series, we’re saving this one for last.

Alright now that we have that out of our system, Whitey had a lot to look forward to in 1982. Despite the strike wiping out 60 games, his Cardinals still drew over 1,000,000 fans and were on pace to push past 1.6 million, although that number likely would have been higher as ticket sales had begun to rise toward the beginning of the strike when the team sold nearly 80,000 tickets ahead of their series against the Giants. Newcomer Darrell Porter did what Whitey kind of expected him to do, which is get on base at a .364 clip despite batting .224. George Hendrick, whom they picked up in a trade with the Padres in 1978, slugged 18 homers and carried a .841 OPS. Bob Forsch won 10 games, trade acquisition Larry Sorenson led the team in innings pitched, and Bruce Sutter saved 25 games with a sub 3.00 ERA.

Transactionally Whitey made one inseason move and that was shipping outfielder Tony Scott to the Houston Astros for a temperamental right-handed pitcher named Joaquin Andujar. To say Andujar was a firecracker would be undermining firecrackers everywhere, Joaquin constantly feuded with then-manager Bill Virdon, a close friend of Whitey’s. It wasn’t uncommon for Andujar to tear up a clubhouse from time to time or offer some A+ quotes to the press. In a game in which he gave up a 3 run homer he said he wished he had a gun so he could shoot himself. Whitey called him Goombah, and figured what the hard-throwing Dominican needed was some positive reinforcement. In desperate need of pitching to shore up a club that ranked bottom 10 in team ERA, the White Rat rang up his friend and offered to take him off his hands.

In the offseason Whitey would have to juggle Andujar’s free agency with his typical wheeling and dealing swagger. Both parties were in agreement on a 3 year deal, but Andujar wanted $2 million and the Cards countered with half that amount. Joaquin spent about a month as a free agent and even got picked by 11 teams in the re-entry draft, but as the new year approached he worked out a deal with Whitey and signed back with the Cards.

Herzog still had blockbusters to complete. On October 21st, while game 2 of the World Series was being played, he pulled the trigger on sending club union rep Bob Sykes to the New York Yankees for a gangly 7th round outfielder named Willie McGee.

Around Thanksgiving Whitey went sizzler when he put together a 3-team trade involving Cleveland and Philadelphia. He sent Sorenson and Silvio Martinez to Cleveland who sent Bo Diaz to the Phillies. The Cardinals got a pigeon-toed outfielder named Lonnie Smith in return.

Lonnie was integral to the Phillies success despite never being a full-time starter. In 1980 he hit .339 and stole 33 bases in 331 plate appearances. In ‘81 he played in 62 games and became a full-time starter in September where he finished the season with a 23 game hitting streak and 21 stolen bases. With aging slugger George Hendrick turning 32, Whitey wanted to move him to a corner spot to preserve his legs, he found his replacement in Lonnie.

Which brings us to the final blockbuster trade that ultimately set the Cardinals up for the rest of the decade. In the previous offseason Whitey mentioned that his shortstop, Garry Templeton, was the only untouchable player heading into Winter Meetings. Tempy had a lot of god-given ability, for starters he could hit the shit out of the ball; his 753 hits from 1977-1980 were fifth most in the majors at that time and his total zone rating sat at a respectable 8. In 1979 he became the first player in MLB history to collect 100 hits from both sides of the plate. Before 1981, Garry was a .300 hitter and a triples machine. He always took time to shop at the gap and his 59 three-baggers during that span topped the Majors by 9, and while he wasn’t the most prolific base-stealer, Whitey could count on him to swipe 30 bags a season.

But Garry Templeton was a bit of a headcase in the eyes of his surly Midwestern manager. Whitey had placed him the DL earlier in the season for a chemical imbalance, and their relationship was deteriorating fast when Garry told him he didn’t want to play day games anymore because he was usually too tired from the night before. The flummoxed Whitey looked at him and said, “What’s the matter with you? You’re tired? Get your damn rest!” According to Whitey, Garry didn’t want to play in Montreal or face certain pitchers, which drove him up a wall especially when, as he put it, he was playing a 32 year-old George Hendrick with no problem. And maybe to compound that more, the Cardinals were currently jousting with the Expos for the 2nd half divisional crown.

Templeton also had a rough relationship with his teammates, and the general consensus that followed him was that you didn’t know which Garry you were going to get that day. He drew the ire of his coaches, fans, and teammates on almost anything he did. He wouldn’t leg out a ground ball or he wouldn’t take out the shortstop on a double play. In modern baseball these kinds of transgressions often go overlooked, one because in most cases they don’t really matter a whole lot–and you can’t kill middle infielders anymore–and two the emphasis on player health. Garry Templeton was sort of ahead of his time in that regard, highly conscious of his body even if it betrayed him at certain points.

But there’s something a little more to that. The physical limitations were an obstacle deployed by Garry’s greatest health concern, his brain. He had been battling depression and anxiety for the better part of three seasons, and after the strike it seemed to creep back in force. Gene Tenace mentioned that the first games after play resumed Garry was a man on fire, but that his play quickly went south. To hear Garry tell it, he had one friend on the team, Tony Scott, who he could relate to, and he was traded to Houston.

I don’t know, man. Garry Templeton is often poked at by older fans for what he did, and yeah it was pretty dumb but even Bruce Sutter admitted that there’s a double standard in how ballplayers are treated and the outrage when one of them finally responds in kind. It’s one of the additional prices of playing the game and making life changing money, I get that, but keep in mind that ballplayers in the early 80s, despite all the gains made in years prior, weren’t raking in the Fuck You dollars that guys make today. Garry Templeton was considered a star on the Cardinals, and if his brain would just let him, he would be a hall of famer according to his manager. He was making $667,000 a year with his current contract, one of the largest on the team, but if you adjust that to today’s standard Garry was hauling in less than $2.4 million a year.

He was often the subject of scrutiny on teams that belly-flopped their seasons, he was told he made too much too fast. When criticizing his talent didn’t do the job, they called his heart into question even when he played hurt. It doesn’t excuse what he did, no, but should serve as pointing out that Garry Templeton had more going on inside of him than an insidious urge to lash out at the people around him. And that, ultimately, what he lacked in mental firepower then he’d find later in his career in San Diego and as a coach for the Angels.

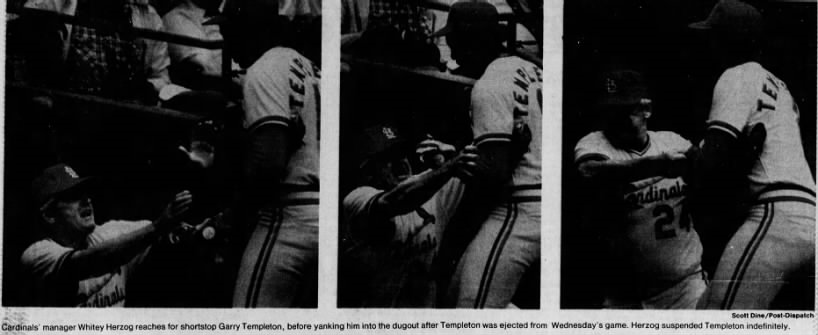

Anyway, it’s Ladies Day at the ballpark. It’s the rubber match of a game against the Giants. Whitey says 12,000 fans were there, baseball-reference says maybe 7,700, who cares. There are people there and they are letting Garry have it. In the first inning he struck out on a ball in the dirt and didn’t run to first. It’s not known if he knew the ball had gotten by catcher Milt Mary, but after the play he gave the booing fans a middle finger salute.

In hindsight Whitey should have gotten his man then, but Garry got two more innings of work in before finally putting a neat little bow on his outburst. Fans jeered him as he went into the field in the top of the 2nd and 3rd. As he was coming off he gave a few of the fans an “up yours” gesture, prompting home plate umpire Bruce Froemming to toss him. Boos rained down on Templeton, but there were few fans who were letting him have it more. According to sports agent Richard Bry, they were tossing ice at him and “calling him a n—–,” although Templeton said they were somehow saying worse things than that. After a couple innings of this he lost it; he was said to be nursing a bum knee at the time–the same knee he said he would blow out and hamper his explosiveness in San Diego–and on Ladies Day at the ballpark, just outside the home dugout, he grabbed his crotch in the direction of the racist chanters and even challenged them to a fight.

Whitey came unglued. Giants manager Frank Robinson said, “I’ve never seen it happen, and I hope I never do again. There’s no place for it.” Garry’s teammates were completely astounded. Whitey rushed to the top step and grabbed Templeton, yanking him into the dugout. Coaches and players peeled them apart. He shouted at him, “Get out of here. I don’t want you on the road trip. I don’t want you around my players. I don’t want to see you. You make $690,000 and you go out and make an ass out of yourself.” Templeton went to the clubhouse, Dane Iorg entered. The Cardinals won 9-4 thanks to a triple hit by Dane, and immediately began distancing themselves from their teammate. Gene Tenace had the most fiery response, saying the Cardinals didn’t need him and that he “didn’t have the guts to apologize to the rest of us. He’s a loser. We’re better off without him.” Another teammate said he didn’t know how anyone could come back from that, and when the team departed for San Diego Garry stayed home. According to the press Garry had betrayed an organizational history of taking in players besieged by controversy outside of their control.

Whitey fined him $5,000 and, after Garry agreed to psychiatric help, placed him on the Disabled List. The news would come out that Garry had been suffering from depression, and although it took a couple weeks, he finally apologized in a press conference to the organization. In a separate meeting with his team, he apologized to them as well. It was a pretty good apology. Dane Iorg said he was 100 percent satisfied, Bruce Sutter expressed empathy and Bob Sykes said Garry said the one thing everyone wanted to hear. Even the prickly Gene Tenace was won over, saying “I can’t go into details but he was man enough to admit. It wasn’t easy for him, but he did it and you’ve got to give him credit.” Garry ended his apology by telling his teammates he loved them all, and later that day went 4 for 5 with 2 runs scored against the Expos–a place he said he hated playing in.

Well, not everyone loved Garry. There certainly wasn’t no love lost from Gussie Busch and Whitey Herzog. Whitey initially held out hope he’d keep him, but changed his tune after his meeting with Busch who told him to “trade the son of a bitch.” When asked by reporters if the heckling fans deserved any blame Whitey said, “Whatever the fans said, he had it coming.” Morris Henderson of the St. Louis Argus, a black newspaper, pointed out that Whitey referring to Templeton as “boy” didn’t help matters.

There’s this stigma that St. Louis fans treat black players differently than others. Dexter Fowler comes to mind, a player who’s hustle was constantly called into question. Templeton would tell the Washington Post a year later that “The fans always thought I was loafing. It’s just the way I play. After five or six years, you’d think they would grow to understand the way I play: fluid.” When Whitey visited him in the hospital Garry promised he’d play hard the rest of the way but that he wanted to be traded in the offseason. From when he returned to the end of the season he’d hit .369 and score 13 runs.

Whitey told the press that because shortstops were at such a premium, whatever trade he’d make for Templeton would have to have a shortstop coming back. He preferred defense over offense, noting that whoever took over would need to be quick-handed to get balls off the turf. He initially wanted Rick Burleson, Alan Trammell, or Ivan DeJesus. Burleson and DeJesus’s best days were coming to an end and they were largely past their prime by 1984. Trammell would have a Hall of Fame career with the Tigers. Whitey also thought about Jose Oquendo who he considered the 2nd best fielding shortstop in the National League.

He didn’t consider this right away, but the thought soon dawned on him when his old friend Dick Williams and Padres GM Jack McKeon approached him at the Winter Meetings asking if he’d be interested in their shortstop Ozzie Smith.

Smith had been a defensive wizard for the Padres, winning consecutive gold gloves in 1980 and ‘81. He also had speed, in the four seasons with the Friars he swiped 147 stolen bases in 193 attempts. Ozzie’s main weakness came at the plate where he was an absolutely atrocious hitter. He never hit higher than .258, his rookie season, and had one home run to go along with a .573 OPS, the 3rd lowest among qualified MLB shortstops during that time.

The Padres at first had no interest in shipping Smith, but Ozzie was demanding an extension and was looking for a 5 year deal worth $25 million.

With no hopes of coming anywhere near that figure, they reached out to Whitey to see if a deal could be struck, and on December 10th they agreed to send Templeton and Sixto Lezcano to the Padres.

But things got complicated real fucking fast. Ozzie Smith, despite signing a one-year contract, had a no-trade clause and he wouldn’t entertain the prospect of moving to the Midwest unless he met the man who wanted him. Whitey was stunned, but he really wanted Ozzie, so he hopped on a flight and flew out west to meet him and his agent Ed Gottlieb. What started was a multiple months affair of both sides jockeying the other in a kind of “will they won’t they” dance. Ozzie was impressed with Whitey, but wanted to be cautious about upending his family from sunny California and moving them to the Midwest. His agent wanted more securities for Ozzie’s impending tenure. Whitey hated that, like he hated most agents, but you have to understand that Smith held a lot of leverage. He used that leverage over Padres President Ballard Smith when he found out that Templeton was making over twice as much as him. These talks dragged on into February to the point Herzoghad reopened talks with the Baltimore Orioles about shipping Templeton. Finally, after Ozzie traveled to St. Louis to see the city, he gave the go ahead and the trade was consummated on February 11th. The St. Louis Cardinals finally had their starting shortstop, and after one last second trade before the start of the season that sent Bob Shirley to the Reds for reliever Jeff Lahti, the 1982 Cardinals were ready.

In the years to come Whitey would cement himself as a Cardinal legend, and when he and his team lost their competitive touch, he’d go on to do other things with his time. After resigning from the club in 1990, he’d come out of retirement as a favor to Gene Autry, the owner of the California Angels, where he tried to build a contender from the spare parts left over.

The results were…not what he expected. Disastrous even. He got into screaming fights with his stars, his non-PC demeanor rubbed people the wrong way, he bickered with the front office and got into shouting matches with player agents. He was asked to cut the budget but also field a competitive team. He lost stars like Dave Winfield and Wally Joyner to free agency. He was completely overmatched. People said he was out of touch, not a people person, and that the game had passed him by. He quit that job after two seasons.

I find that incredible. I mean, it doesn’t surprise me Whitey would rub certain people the wrong way. What you see is what you get with him, you get a colorful guy with a lot of brashness and honesty. No, what’s surprising to me is that in 10 years the game transformed so much that he became largely irrelevant in it. That the mindset he embodied to pull off blockbusters, to build HIS team, didn’t translate into success not even 10 years into the future. It’s kind of incredible.

Whitey’s relationship to labor has always been a complicated one. He’s a complicated man, he contradicts himself a lot. Whitey was a player’s manager, even beloved by those who hated him. But he was still management. His best friends were the suits that signed the checks and undercut the people playing a game we all love to watch. Whitey described the players as being greedy, but also said he understood why they got their bag. He talked about getting down on his knees and thanking Marvin Miller in his prayers, but also believed that Miller was “too smart for his own good” and had created a runaway train in player salaries. Miller crafted not just a system that benefitted players, but coaches and trainers, and fans and everyone in between. You probably didn’t know this, but getting MLB pension doesn’t just apply to being a player. Marvin Miller got a visit one time from Joe DiMaggio, who asked him if he could help him with his pension because he got out of the game way too late. And Miller did, along with hundreds of guys like him. He got Satchel Paige a pension. All it cost was a little money from people who had too much of it. I wonder if Whitey really appreciated that? Has he ever?

Baseball teams aren’t owned by small business owners anymore. Fred Saigh was a lawyer who made his money early with a shitty cigarette company. Gussie Busch was just the grown-up son of a regional beer baron. Teams today are owned by billionaires or holding companies with more money at their disposal than some countries. The DeWitts share less in common with the everyday man than the average baseball player, they share zero of the problems and concerns you are worried about.

Starting in 2000 a campaign began to get Marvin Miller elected into the Hall of Fame. He was endorsed by legends like Hank Aaron and Joe Morgan. In 2003 his name appeared on the Veterans Committee ballot and would again in 2007, 2008, 2010, 2011, 2014, 2018, and 2020. Whitey was elected to the Hall of Fame with an 87.5% vote in 2010, Marvin Miller missed the boat at 58.3%. In 2013 Herzog was selected to be a part of the 2014 Veterans Committee.

How do you think he voted? No one knows, voters are not permitted to share their ballots. That committee featured players Rod Carew, Carlton Fisk, Joe Morgan, Phil Niekro, and Frank Robinson, the rest featured media, historians, and front office guys. This committee had Jerry Fucking Reinsdorf on it, I mean c’mon.

Miller received less than 7 votes on that ballot. LESS THAN 7. I think I can probably guess 5 of the guys who voted for him. Marvin had died two years prior from liver cancer at the age of 95. He knew he wasn’t getting in while he was alive, that he wouldn’t be enshrined the same way the Hall showers accolades on executives, but his legacy was more impactful than any baseball president, commissioner, or manager had. In 2020 he finally got in with the 12 needed votes. He should have been in a lot sooner.

Whitey’s own relationship with labor was fractal, yet despite this he was able to take advantage of it and build the team in an image he’d be proud of. While players earned fair compensation, competitive balance, and labor emancipation, Whitey began building a death star that would terrorize the National League for the next five years. He endured a strike and crafted numerous blockbuster trades to construct one of the scrappiest and most efficient teams ever. He now had what he lacked in Texas and Kansas City, he had what he had always been chasing after his whole career.

He had the Runnin’ Redbirds.

Editor’s Note: While we were writing this essay, Cardinals reporter Rick Hummel died. You’ve noticed this by now, and if you haven’t yet you should, but this entire series would not be possible without guys like Rick. Sports reporters get a lot of flack in this business and face a lot of obstacles. It’s hard to get established and maintain a moral line that is consistent to the practices of the craft, and do so for so long at one paper. Rick Hummel did that. There is no 1982 without him and the countless others. We are forever grateful.

Rest in Peace, Commish.

Leave a comment