By Tom

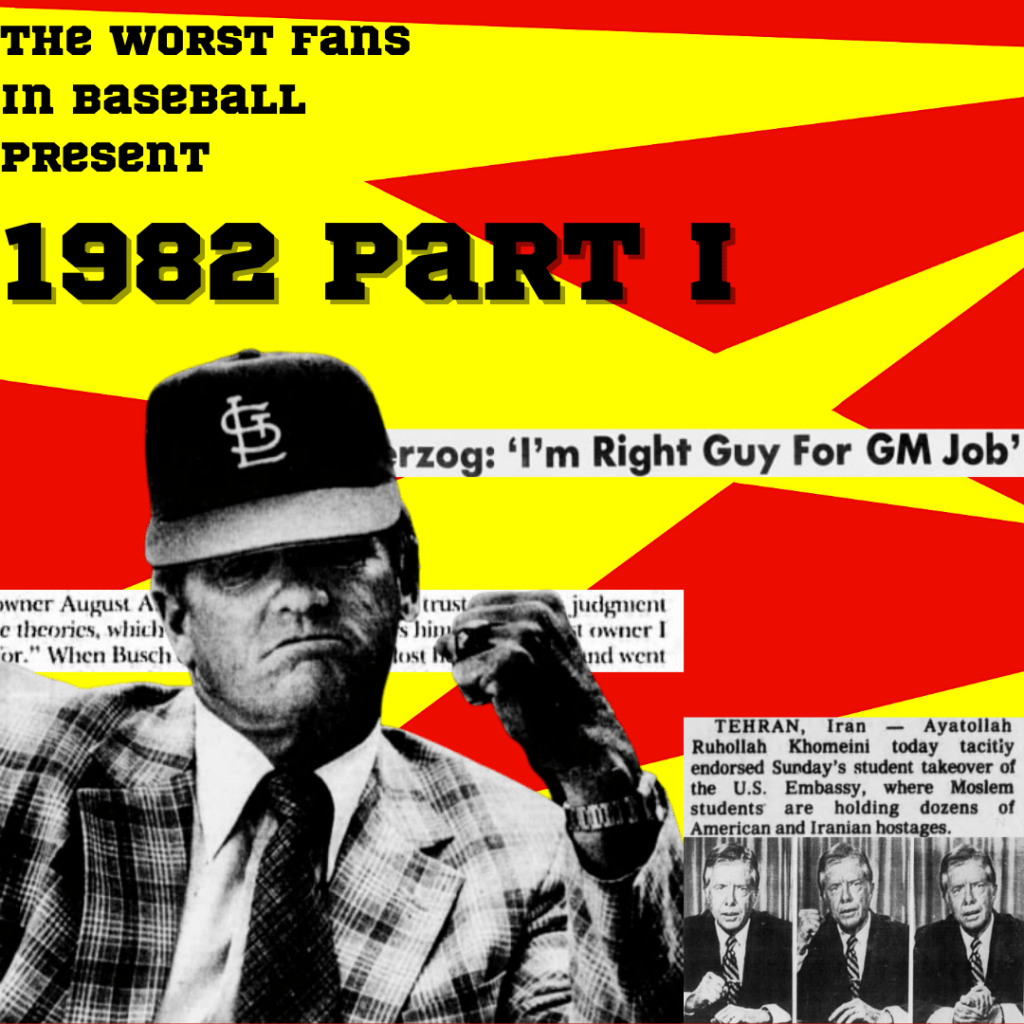

We’ve recently released Part 1 of our docuseries on the 1982 St. Louis Cardinals. If you don’t want to read this article, you can listen to the audio of it right here.

The St. Louis Cardinals are a baseball organization that’s been in existence since 1882 when they went by their original name, the St. Louis Brown Stockings; they eventually settled for Cardinals but not after a 16 year run as the Browns and a one year run as the Perfectos. This franchise is 140 years old, or 122 years young if you’re going by Cardinals years, and just like anyone who’s made it that long they’ve seen some shit.

This organization is one of the most storied around. But it wasn’t easy at first. When St. Louis transitioned to the National League in 1892 they didn’t enjoy a winning record until ‘99 when they were the St. Louis Perfectos. When they became the Cardinals they spent the 1900s keeping the basement tidy. It wasn’t until the 1920s with the help of Hall of Famers like Jesse Haines, Jim Bottomley, and Rogers Hornsby that this organization started to write some good stories.

The Cardinals to this day, have won a National League leading 11 World Series in their lifetime, each of them memorable in their own right. There was no secret formula to their sustained success. The 1926 squad ended Game 7 pitching a 39 year-old Pete Alexander, who walked Babe Ruth in the 9th who got thrown out trying to steal second to end the series. The 1940s club won 3 championships through sheer overwhelming firepower. The 2006 Cardinals limped into the playoffs with an 83-78 record, before dispatching two division winners in the Padres and Mets, and eventually the 95 win Detroit Tigers. Hold a microscope over each of these teams and we’ll find oddities so minute they’re almost miraculous.

The 1982 squad won their World Series by adopting an unconventional style. They played a style of baseball that was, at the time, thought to be forgotten. They took advantage of their stadium’s expansive outfield and artificial turf to create one of the best defenses for the decade. They hit the least amount of home runs, but won the fifth most amount of games. When they started the decade they struggled to draw in a million and a half fans, by the end of the 1980s they had doubled their attendance. They were called the Runnin’ Redbirds, and they won by becoming their manager.

The early 1980s in America was a period of recovery from years of dejection and political despondency. The nation was not even a decade removed from the stinging defeat of the Vietnam War, as well as a political scandal that saw the then-current president resign, and what seemed like a never-ending economic recession. The 1970s were filled with crises that seemed to repeat themselves every other year. Following the fallout of the Watergate Scandal, Gerald Ford pardoned Richard Nixon; his vice-president Spiro Agnew–a man described by the Maryland Bar Association as being “morally obtuse”–paid only a fine for felony tax evasion and nothing else; a couple years later and, under a new administration, Jimmy Carter commuted Nixon operative G. Gordon Liddy’s sentence for his role in Watergate. Liddy is the definition of an American patriot, like the time he organized a different break-in of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist, or when he volunteered to assassinate newspaper columnist Jack Anderson; he also volunteered to kill Ellsberg too for his role in releasing the Pentagon Papers. Sorry to go on a tangent, but my favorite Liddy fact was during his time in prison he would respond to black inmates insulting him by singing the Nazi anthem. Just a swell guy.

Most infamously the 1970s and early 1980s were plagued by economic instability. In 1973 OPEC enacted an oil embargo on nations that supported Israel in the Yom Kippur War, this coupled with the shit ton of money spent in Vietnam and a series of tax cuts starting under the Kennedy Administration would create an unstable economy. We know you’re here for baseball, but it’s gonna be important to remember this later. The recession that followed the Oil Crisis sparked a rare phenomenon that doesn’t happen a lot. We’re not economists, we’re drunk Cards fans, but some economic terms that might leap out to you are inflation and unemployment. Inflation is the price of goods and services, employment rate is the amount of people in the workforce. Usually in episodes of economic regression, one can be used to combat the other. High unemployment rate? The government can pass policy or spend some money or adjust interest rates. High inflation rate? Time to cut back on all those measures and let the unemployment rate go up. It’s way more complicated than that, and honestly we’ve spent too much time reading off what Forbes has to say about it. But the gist of it is, when inflation is high unemployment is low, when unemployment is high inflation is low, which creates this very fragile balancing act on how many people shouldn’t have a job to keep the price of milk down.

Anyway, both of these bad things happened in the 1970s. High unemployment and inflation created a new term called stagflation. The stock market crashed on a level matched only by the Great Depression–eventually surpassed by the 2008 Recession. High inflation rates would continue into the 1980s, despite the American economy growing under the Carter Administration. Over 2 million people lost their job in this three span. The 1970s were a period of malaise, the post-war American nationalism that dominated the globe was emasculated.

It then all happened again in 1979! In the early 1950s Iran’s Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh enacted a series of popular land and wealth redistribution policies, but in a more pressing maneuver he nationalized his country’s oil fields. The United States and Great Britain didn’t like that, so they backed a coup d’etat in Iran ousting a democratically elected leader in favor of a monarchical authoritarian regime! Isn’t that…neat, certainly won’t happen again.

Beginning in the 1960s the US-British backed Shah began a series of cultural and economic reforms that backfired when the economic divide between Iran’s working class and their aristocracy widened. In 1978 Iranian fundamentalists led by Ruhollah Khomeini began a revolution that ousted the US-backed Shah a year later. The global market recoils, Iranian oil workers strike, Khomeini goes to war with Iraq in 1980, and now one of the world’s leading oil producers is suddenly not meeting the demands of the US. Ladies and gentlemen, I present to you the 1979 Energy Crisis.

In 1979 a group of Iranian college militants stormed the US capital in Tehran and took 52 American hostages and held them captive for almost a year and a half. A lot of historians point to this as the end for Jimmy Carter, but really the death knell for his administration has to be the impending recession, something his administration had worked years trying to curb following the last one. We can shit on the Iranians all we want, but we drew first blood, we kind of deserved what they’re about to do to us. You play schoolyard bully long enough eventually someone’s gonna get tired of your bullshit and pull your pants down. In 1980 Jimmy Carter loses re-election in a monumental landslide. After 444 days in grueling captivity, the 52 hostages in Tehran are released on January 20th, 1981, the same day as the inauguration of Ronald Reagan.

We’re gonna need to spend a lot of time talking about a specific guy. The ‘82 Cardinals have a lot of them, but this one is the straw that stirs the drink.

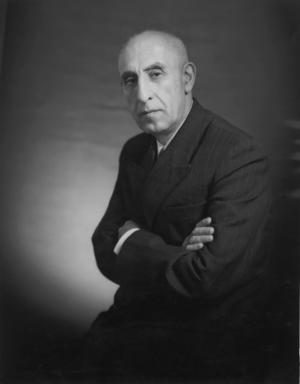

Dorrel Norman Elvert Herzog is a character.

Before he invented a new way of playing baseball on plastic fields, he had a popular nickname that everyone called him; Relly. Relly was the middle child of Herman and Codell Herzog, and baseball was their life. They came from the small town of New Athens, a rural town about 40 miles east of St. Louis in Central Illinois. So much of it reminds me of my small town in Southeast Missouri, if you come from a small-town you’d probably feel the same way.

During the early 20th century it was a farming and coal-mining town with a couple lumber mills. Like a lot of long-standing communities through the Missouri-Illinois corridor, it was predominantly German. It has about 2,000 people now, and hasn’t changed much since Relly’s time, when the number of local denizens sat around 1,500.

Relly and his older brother Herman were pretty good ball players. Their brother Codell not so much, but he was the guy we most relate to. A stats and numbers guy, he took one at-bat for the high school team where he hit a dribbler back to the pitcher. He didn’t even run to first he just went to the dugout and called it a career there. That’s a funny guy.

Growing up in this part of the country wasn’t easy. The boys’ parents Edgar and Lietta Herzog eked out a living for their sons. Edgar worked at a brewery until it burned down and then took a job as a part of a highway crew, his mother worked at a shoe factory. Relly described his mom as a very clean and strict woman, so much so that he spent most of his time out of the house. His dad had the distinction of never missing a day of work at the local brewery, and imparted his sons with the wisdom of: “Be there early and give them a good day’s work, so when it comes time to lay someone off, it’ll be the other guy.”

This was a different time. Hard-work was a virtue and part of your identity. Relly grew up through World War II and graduated high school in post-war America. This was when the American Dream wasn’t an illusion, where that kind of gumption and moxie could be rewarded. Today’s go-getter hustler types sell bullshit crypto and NFTs, they promote MLM schemes and labor exploitation. It’s not their fault, they’re a feature of today’s capitalist system.

If it sounds like there’s some friction between Relly and his dad, there was. The Herzog boys had to hustle for their money. Every morning he’d get up at 6, deliver newspapers. He’d sell bakery goods off a truck, he dug graves for money and worked at the same brewery as his dad before it burned down. In 1992 a LA Times reporter asked him if he was close to his father, and Relly looks pained to answer, almost defensively: “Every kid is close to his father, isn’t he?” and then a moment passes and that feeling that every kid who grew up a little harder than the rest subsides. He said, “We were poor. Dad drank a lot. Women did the work. He never talked to me. The goddamn Germans are like that. My father only asked me if I needed money when he knew I had it. I supported myself since the seventh grade.”

Growing up he was very talkative with people outside his family. His friends swear he had a great singing voice, and he was known as very good with women through his younger years. One writer described him as a real “guy’s guy.” An expose on him right after he took over GM duties for the California Angels portrays a chatty and lively man. Sure, this piece highlights him rapping off various sexist, racist, and homophobic jokes. But his players love him, and he signs autographs for fans that come up and talk to him and then he comments to writer Pat Jordan that all the jokes he makes will hurt his Supreme Court nomination. He’s a funny and charismatic guy, and he needed all that growing up.

He’s a funny and charismatic guy, and he needed all that growing up.

His brother Herman had a speech impediment that undermined his confidence and made him less audacious as Relly. It may be one of the reasons why after 1954 his professional career didn’t pan out the same as his middle brother’s. Relly knew he wasn’t going to college, and although he reckoned himself as a better basketball player, he was obsessed with baseball. On days when he could, he’d hitchhike up Belleville and take a bus to St. Louis where he’d pay a buck 25 to watch the Redbirds at Sportsman’s Park.

He was captain of the basketball team his senior year, and although he wasn’t a great shooter he still drew interest for his ball-handling and speed from SLU and Illinois. He didn’t follow in the path of his brother Herman, a shortstop, instead Relly was an outfielder/first baseman prototype who pitched a little too. In his junior year the 5’8” 130 pound Herzog led the team with a .584 average and took the New Athen Yellow Jackets to the state championship where they lost to Granite City 4-1. It’s something he never quite got over and would follow him all the way through his managerial career. It’s one of the first things he addresses when he finally gets the monkey off his back.

Herzog played in the Yankees system but was passed over for a guy named Mickey Mantle. He likes to point out that he got a larger sign-on bonus than Mantle by about $1,000. He was traded and bounced around and got real sick in 1963 with the Detroit Tigers where he called it a career after slashing .151/.303/.226 in 52 games. He never played enough games to qualify for a batting title. When asked about his release years later Herzog said, “We can’t all be Mickey Mantle, can we?”

But it’s during this time that Relly comes to know a few things. The first one comes when he’s playing in the Yankees D-League for the McAlester Rockets. We can’t find anything too concrete, but it’s during this time that a sportscaster noticed that Relly had some very blonde hair, and either because they forgot his name or hated him, they started calling him Whitey. Years later someone would point out that he bore a striking resemblance to Yankees pitcher Bob Kuzava, almost like a White Rat.

It was before his retirement, maybe he knew he wasn’t cut out for this playing crap. Whitey joined the Army Corps of Engineers during the Korean War. While he was stationed at Fort Leonard Wood he managed the camp’s baseball team and found he had a knack for it. During Spring Training in 1955 legendary Yankees manager Casey Stengel took Whitey under his rein, as if almost sensing he’d become a manager in the future. After he traded him to Washington Stengel assured him he’d get him back if he had a good year. Whitey didn’t.

Herzog was offered a job by Kansas City A’s owner Charley Finley in 1964. He pounced on it and became a base coach for the A’s in 1965. When Charlie Finley refused to give him a raise he told them to get their donkey to coach first base and headed to New York where he became the Mets director of player development for the next 6 years. He was Gil Hodges’ successor for managing duties whenever he would decide to step down, but Hodges died suddenly of a heart attack and the job went to Yogi Berra. Whitey saw it as a snub and took a 2 year contract to manage the Texas Rangers. A team that lost 100 games the previous season.

I’m sure it hurt a little bit. Whitey didn’t complete his contract with Texas, hell he didn’t even make it through his first full season. At 47-91, he was fired and eventually replaced by Billy Martin. Over in the National League fucking goofy-ass Yogi Berra led the Mets to an 82-win season in the god awful NL East, and took them to the World Series where they lost to the Charlie Finley’s now-Oakland Athletics in 7. They did this with players he scouted for them, and lost to the team he was a coach on less than a decade ago.

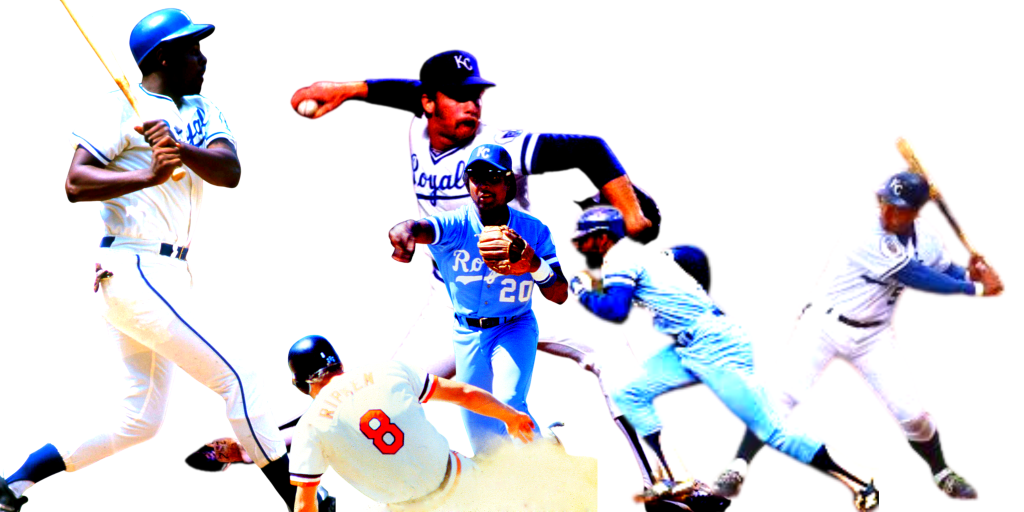

Following this he coached some bases for the Angels before getting a call from the Kansas City Royals in 1975. The Royals had just fired third year manager Jack McKeon after a 50-46 start that saw them recently come off a 2-10 stretch. The abrasive McKeon had lost the locker room and Royals GM Joe Burke was looking for someone to fill the void. Burke was GM for the Rangers when he hired Herzog to steer that team, and he too got the boot by the end of September. They were friendly, although by the end of Whitey’s tenure they’d have a more complicated relationship. Whitey was on a shortlist that included KC native Hank Bauer, Orioles Billy Hunter, and…oh shit. Is that Billy Martin?

Whitey’s had his struggles with the front office, but nothing quite like Billy Martin. He was fired after one season with the Minnesota Twins. This wasn’t a bad team or performance, they won 97 games and went to the ALCS, but Billy Martin had a reputation for being a bit of a prick as well as a drunk. He kicked the vice president out of the locker room, he got plastered on road games, and when asked by GM Calvin Griffith why he would do the things he did Martin would reply “because I’m the manager.”

After the Twins he went managed the Detroit Tigers for 3 seasons, made the playoffs in ‘72, regressed the following year where his off-field antics followed him from Minneapolis and after criticizing the front office publicly he was let go. Oh, and then there’s the Rangers, the team he took over from Whitey.Rangers owner Bob Short, who made a fortune selling plumbing pipes, said he’d fire his own grandmother to hire, Billy. The Rangers won 84 games the next season and Billy Martin AL Manager of the Year, but hold up you know where this goes!

Martin couldn’t stop his excessive drinking, he struck a male traveling secretary on the road, he publicly criticized the owner by saying he “knows as much about baseball as I do about pipe,” and the coup de grace of all this was on July 20th he had the stadium PA play “Thank God I’m a Country Boy” during the 7th inning stretch, after which he was immediately fired. Goddamn, dude. What a…what a real asshole, god they don’t make them like they used to.

You’ll notice a trend here about Whitey if you haven’t already. Whitey was the best at everything he did. He routinely touted he was the best manager in the NL, and when pushed back on that he’d cite a 1983 player’s poll that voted him best manager to play for. His departure from the Mets was a rocky one, but on the way out he assured he was the best they ever had. He scolded the Rangers team and front office, saying they were “the worst excuse for a big league club I ever saw.” He demanded the A’s pay him more as he thought he was their best coach despite no experience at the time. And to be fair, he could back all that up. Finley touted him as his best coach in ‘65, the Rangers improved but didn’t fare much better under Billy Martin, the players he scouted and developed took the Mets to a World Series win in ‘69 and an appearance four years later. As a GM he was well respected by scouts and his competitors, Cleveland GM Hank Peters once said, “He don’t lie. If you’re horseshit, he tells you to your face, he’s the best judge of talent I ever saw.” Whitey was more sensitive than he let on, perhaps this was a result of his rougher upbringing, and how the undersized outfielder was passed over again and again and came up short in the spur of the moment. Sure he was very defensive, but much to his credit he often backed it up.

McKeon’s tenure brought a lot of instability to the Royal’s clubhouse. While he wasn’t the authoritarian like Martin, McKeon was said to have been a negative and critical presence, he failed to communicate to his players and take any advice that didn’t come from him or his yes men. He didn’t get along with the press, even though papers like the Kansas City Star would go out of their way to say he was a competent baseball strategist. He didn’t have that leadership quality for a big league club yet. Trader Jack would win a World Series almost 30 years later as a 72 year-old for the Florida Marlins, his only playoff run, and he holds a couple unique distinctions as the only MLB manager with a 1,000+ wins with less than a 1,000 losses, and the only manager with 1,000+ wins at both the Major League and Minor League level. After feuding with bench and hitting coaches through Spring Training, starting pitcher Steve Busby threatened to quit the team. In July Jack was let go.

This kind of instability would be a lot for anyone. Hank Bauer had been out of the game for over 5 years, Billy Hunter had no managerial experience despite being a 3rd base coach for 14 years. And we just gave you over 250 words about the Shit Show Express that is Billy Martin. If Joe Burke was gonna find a suitable replacement he’d have to turn to an old familiar friend, it had to be Whitey.

If Joe Burke was gonna find a suitable replacement he’d have to turn to an old familiar friend, it had to be Whitey.

Kansas City sports reporters were content with Herzog’s pick, who immediately after his hiring said he was going to go hang out with his players. I’m not kidding, he wanted to know his players better and get a feel for them. He’d go on to write how he wasn’t like his friend and colleague Dick Williams, another legendary manager, who preferred to present himself as an authority figure. Whitey bonded with all his players, learning their wives and kids names. He spent more time with his bench players than he did his stars. He took players fishing, he drank beer with them. He would bet players a dollar for hitting the ball on the ground or behind the runner during a hit and run, a technique he deployed even in his first job in Texas. If there’s one thing you’ll learn about Whitey is that he’s going to come off as a very complicated and sometimes contradictory man; he’ll develop this opinion that baseball has been made worse by greedy players and agents, that money has ruined the relationship between players and managers and especially fans. But his one constant, the one principle he won’t compromise over about the game, is that baseball is about people.

At the time Whitey’s assessment of the Royals were that they were a good but inconsistent hitting team, solid defensively, shaky pitching, but elite speed. He saw potential with this squad, but he saw a lot of potential in the stadium they played in because it had AstroTurf. The use of Whiteyball is credited by baseball writer Bill James as being one of the most impactful strategies to affect baseball. Today only five teams have fake grass of some sort, but during the 1970s 11 teams had turf fields, with a 12th joining in 1982 with the opening of the Twins new stadium. The first use of it came in 1965 at, you guessed it, the AstroDome. The product mirrors a lot of the anguish from the 70s we mentioned; it was cheap, easy to deploy, but most of it all it was multi-purpose. A lot of stadiums that sprang up in the 70s and 80s were also home to football teams, and a lot of these teams were in the National League. By 1982, 8 of the 12 teams that had Astro Turf resided in the NL.

It’s in Kansas City that Whitey begins developing this new technique to play to the Royals spacious outfield and their fake grass. By 1982 he’ll have perfected it. Constructing a team like that was simple in his eyes; speed and patience. Speed to cover alleys, steal bases on the turf, and take the initiative on balls in play. In addition to speedy fielders and aggressive baserunning, Whitey also believed in the idea of a super-bullpen and lefty-righty matchups, not entirely unheard of for his time, but rarely did a manager play the matchup game quite as aggressively as the White Rat.

After taking over for McKeon and getting a knack for his crew, the Whitey-led Royals won 15 of their next 20 after Whitey’s hiring. In typical Whitey fashion he stepped on a few toes by benching fan-favorite Cookie Rojas, but in his place he started the rookie Frank White, who by the end of his 18 year career in Kansas City would play in 2,324 games, second most in franchise history behind teammate George Brett. In fact the top 5 Royals in games played were all teammates during Whitey’s era and the years that followed, a true testament of loyalty. With a new sense of pride these Royals almost willed themselves back into division contention against the mighty Oakland A’s, but that 11 game deficit at the end of McKeon’s tenure was too much for this red-hot ball club.

Whitey turned Kansas City into a juggernaut for the next 3 years. In ‘76 they hit nearly as many triples as they did home runs, they also stole the 2nd most bases in the AL with 218. Their team ERA ranked 2nd in the AL, relievers Mark Littell and Steve Mingori led a bullpen that posted 35 saves. At the end of the ‘76 season they had won 90 games and the AL West crown. One of his contract stipulations was a $50,000 bonus if the Royals drew over 2,000,000 fans a season, something Whitey coerced Burke into writing into his contract, and while the Rat will tell you he hit that number every season, the truth was about half. Nevertheless attendance went from 1.15 million in 1975 to 1.68 in ‘76, and by 1978 Whitey was clearing 2 million with ease.

This ‘76 squad, led by not a single hitter with 20 home runs, had a date against the 97-win New York Yankees, who were managed by Billy Martin.

Sports are not as simple as good vs. evil. Rarely is something easy as a righteous cause is reified in a sport so heavily based on luck. Perhaps Billy Martin is Whitey Herzog’s mortal enemy, his arch rival. He took his job once and nearly did again. The Bronx Bombers had the 2nd best offense and best pitching staff in the American League, they were led by Thurman Munson in his MVP season and last year’s Cy Young runner-up Catfish Hunter. They wrapped up their division so early in September that not even a 4 game sweep to the second-place Baltimore Orioles could worry them.

The Royals had no MVPs or Cy Young winners, they could steal but had to manufacture runs. They led the AL with 71 sac flies, their first baseman John Mayberry leading the league with 12. Last year Mayberry posted a 168 OPS+, the best in all of baseball, this season his OPS dropped 300 points to .663. Didn’t matter, he drove in 95 runs. The Royals held a 12 game divisional lead in August but nearly squandered it when they dropped 9 of their last 11 for the season to finish 2.5 games ahead of Oakland.

This will begin three consecutive trips to the ALCS, all against the New York Yankees, and each time Whitey’s Royals will come up short. In 1976 Mark Littell gave up an iconic walk-off homer to Chris Chambliss. Yankees owner Geroge Steinbrenner will comment that the best manager didn’t win that night, much to Billy Martin’s chagrin. Hearing Whitey describe it, he doesn’t really blame anything else that happened in the game except for one thing, when he swapped 6’2” centerfielder Al Cowens with 5’8” Hal McRae. You can watch the homer yourself, but Whitey states that that the ball cleared the fence by only 6 inches, and that if he didn’t make that defensive swap things might have been different.

In ‘77 Herzog’s Royals would win 102 games going 24-1 from August 31st to September 25th. These same Royals labored the first 2 months, entering June 21-23 before going on a 81-39 tear that saw them take the division by 8 games. In addition to sporting the 2nd best basestealers, Whitey also 4 guys with 20 or more home runs. He had starter Dennis Leonard, who baseball legend Peter Gammons described at the time as having the 3rd best slider in the game, along with 18 game winner Jim Colborn and a tried bullpen that had 3 guys with 10 or more saves. What they didn’t have, and what Whitey lamented, was a stopper.

Even before his firing Whitey would develop an incredibly tense and fractured relationship with owner Ewing Kauffman and GM Joe Burke. Herzog never really felt in control, and while he had a good squad he didn’t have the authority to build and shape a team in his image, a winning image that took advantage of the stadium’s plastic grass and big dimensions. In Whitey’s view Kauffman didn’t care about winning, or the people he employed, and wanted to take credit for everything. He personally hated that Whitey convinced Burke to add that attendance clause, going so far as to say Herzog had nothing to do with drawing that many fans. Kauffman and Burke told Whitey to basically forget free agency, because they wouldn’t sign a player to a contract larger than George Brett’s, and they held to that. Their only free agent signing was a utility infielder named Jerry Terrell and it was for $40,000. When Whitey asked both men to go after free agent pitcher Goose Gossage they told him no, and when the Yankees scooped him up for $600,000 and trotted him out to the mound Whitey could only counter with…fuckin’ Doug Bird.

The Yankees rallied from a 3-1 deficit in the deciding Game 5 to win 5-3. The next year they mopped up the Royals in 4 games. While the Yankees spent every last of their resources to field an army, the Royals were too busy pinching-pennies. Whitey described it as going into a duel without a musket. In 1979 the Royals finished in 2nd place, four games out from the division winning Angels. And despite setting a franchise record for attendance that season, Ewing Kauffman fired Whitey. He thinks the final nail was him not wanting to play Clint Hurdle, a local talent who won Minor League Player of the Year. He recalls getting into a screaming fight with Burke when he asked that Clint be demoted for bad defense. The death knell came sooner, honestly. The Burkes and Kauffmans had a different philosophy than Whitey, one that centered around money, egoism, and frugality. In Herzog’s mind, they weren’t about people. During the 1980s there was a sort of reconciliation with baseball’s connection to drugs in the 70s and 80s. In ‘85, in exchange for immunity, numerous current and former Pittsburgh Pirates players–along with others–testified about their struggles with amphetamines and cocaine. Whitey managed a lot of these guys, like Darrell Porter and Willie Wilson. When he went to Burke and Kauffman to try and get help for the situation they called him a liar and kicked him out of their office. He was gone the minute he started. Whitey would later say that when Burke was on his deathbed he’d tell him he was right about a lot of things, especially Clint Hurdle.

When you read what he had to say about his time in Kansas City you feel like you’re reading a man who thinks he’s cursed. He said, “All my life, I’ve been good enough to get my team close. That was true when I was a kid, and it was truer still when I coached and managed.” He recalls losing a state basketball game his junior year by a point in a game where he missed 3 free throws; he recalls that baseball game where he missed the flyball; he brings up swapping out McRae in ‘76 or letting Larry Gura stay in too long in ‘77. He regrets not putting his foot down even though he knew he was going to be fired. Even after he got the monkey off his back in ‘82, Whitey felt cursed from the Denkinger call or losing Coleman in a freak accident, he lost his two best hitters in Terry Pendleton and Jack Clark in ‘87 when he took the Twins to 7 games. Until he was finally inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2010, he feared those curses he could never overcome would keep him out of Cooperstown.

But that’s not the story we’re going to tell you.

Whitey hated every owner who hired him. Well not every owner. He respected Charlie Finley, although he’d go on to say the man was a control freak with a bad ego. It’s an interesting trend about wealthy baseball owners, they can’t seem to not think their shit doesn’t stink. But there was one guy Whitey respected and that was August Anheuser Busch Jr. You probably know the name as that of the St. Louis beer baron, but Gussie Busch should be more famous for being the man who saved baseball in St. Louis. Previous owner Fred Saigh, like all rich assholes, evaded taxes for a few years until he got busted. He spent six months in prison and when he got out he was given the ultimatum to either sell the team or be banished from baseball. At first Saigh couldn’t find a buyer in the area, this was due in some part to the schemes of St. Louis Browns owner Bill Veeck who encouraged investors from out of town to make bids on the team. Veeck would move the Browns to Baltimore the following year. A consortium of Houston businessmen were set to make an offer and planned to move the Cardinals to Texas, but out of nowhere came Gussie fucking Busch, who convinced Saigh to sell the team to him for $3.75 million out of civic duty.

It’s June 1980, the St. Louis Cardinals suck ass under manager Ken Boyer. Boyer took over for Vern Rapp in 1978 and won 86 games in ‘79. But this year is brutal, as the 49 year-old Cardinal legend saw his team drop 13 of 14 in a two week May span. After dropping the first 3 of a 4 game series against the Expos, Boyer was shown the door. This is a team with some big contracts and not a lot of discipline; they blast music in public or in the clubhouse after a loss, they get drunk in their hotel rooms, and they don’t hustle on the field.

Their lackluster play prompted Cardinals first baseman Keith Hernandez to say this team was the worst he ever played on. By the time news came of his firing, Ken Boyer said he had expected it and that he didn’t feel anything. He was fired in between a doubleheader, prompting coach Jack Krol to take up the mantle for game 2 and lead the Birds to a 9-4 loss and a 4 game sweep.

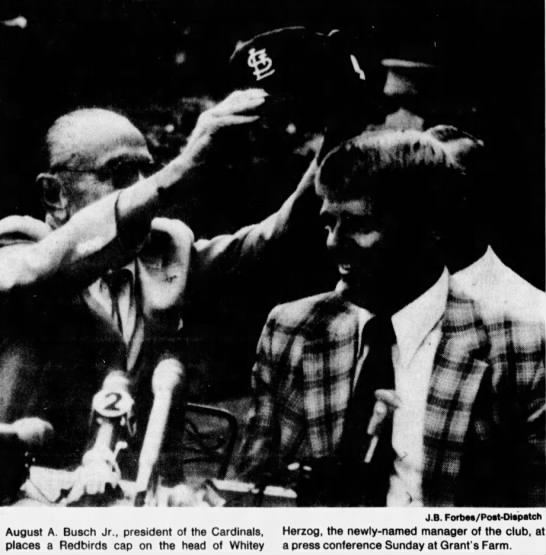

Cards GM John Claiborne, sensing the shifting tides, worked with Whitey under Bing Devine during their tenure with the Mets. Claiborne told Herzog that if he ever became a GM he’d want Whitey as his manager. When Kauffman canned Herzog in 1979 Claiborne immediately called Whitey and asked him if he wanted a job. Whitey said manager. After a 6-20 stretch, Claiborne called Whitey to come out to Grant’s Farm and meet Gussie.

Gussie Busch had a reputation for only offering one year deals to his managers. Whitey saw a lot of himself in the 81 year-old beer magnate, saying they both were a couple of squareheaded, no-bullshit, midwestern Germans. He said Busch loved testing people to see what kind of mettle they had, and if he liked you he would trust you with his life. In the years to come, Whitey would hold Gussie in high-esteem and when the old man died in 1990 it kinda zapped the Herzog’s love for the game.

Busch’s offer was one-year for $100,000, far less money than Whitey was making in KC. Herzog didn’t mince words, he never did. He told him that he won three consecutive division titles and finished in 2nd place once. It wasn’t going to be about the money, but about the commitment. He told Gussie Busch, “Thanks for the offer, but I’m not signing anymore one-year contracts.” He shook his hand and headed for the exit.

But Gussie Busch wouldn’t let Whitey walk. As he would say later in the week he was impressed by this “very opinionated, hard-head Dutchman” and that Whitey was his type of manager, no argument. He told Whitey to stop and sit down. He told Whitey, “The damn players get five year contracts, you can get a three year sonofabitch.”

Leave a comment